Extended hours during "Kirchner. Picasso": Thur. & Fri. 10 a.m.–8 p.m.

Kirchner. Picasso

An exhibition by the LWL Museum für Kunst und Kultur in Münster (September 26, 2025 – January 18, 2026)

From the vibrant life of the big city to the intimacy of the studio and the stillness of the mountains: At the beginning of the 20th century, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Pablo Picasso bore witness to a new era, with their works speaking of change, crisis and passion.

Experimental and innovative, unafraid to search for new forms of expression beyond artistic and social conventions: as key figures of modernism, Kirchner and Picasso continue to shape our perception of this era of upheaval to this day.

… even a child must see that P[icasso] creates in a completely different way and from a completely different position. Hopefully, there will someday be an opportunity to show Picasso´s and my works side by side on a wall […]

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, 1933

Chapter 1:

Two Artist Biographies

Two artists, four countries

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Pablo Picasso were born just one year apart—one in Aschaffenburg, Germany, the other in Málaga, Spain. Although their paths never crossed during their lifetimes, their visual worlds repeatedly converged, and they consistently translated their shared themes and motifs into their own unique languages.

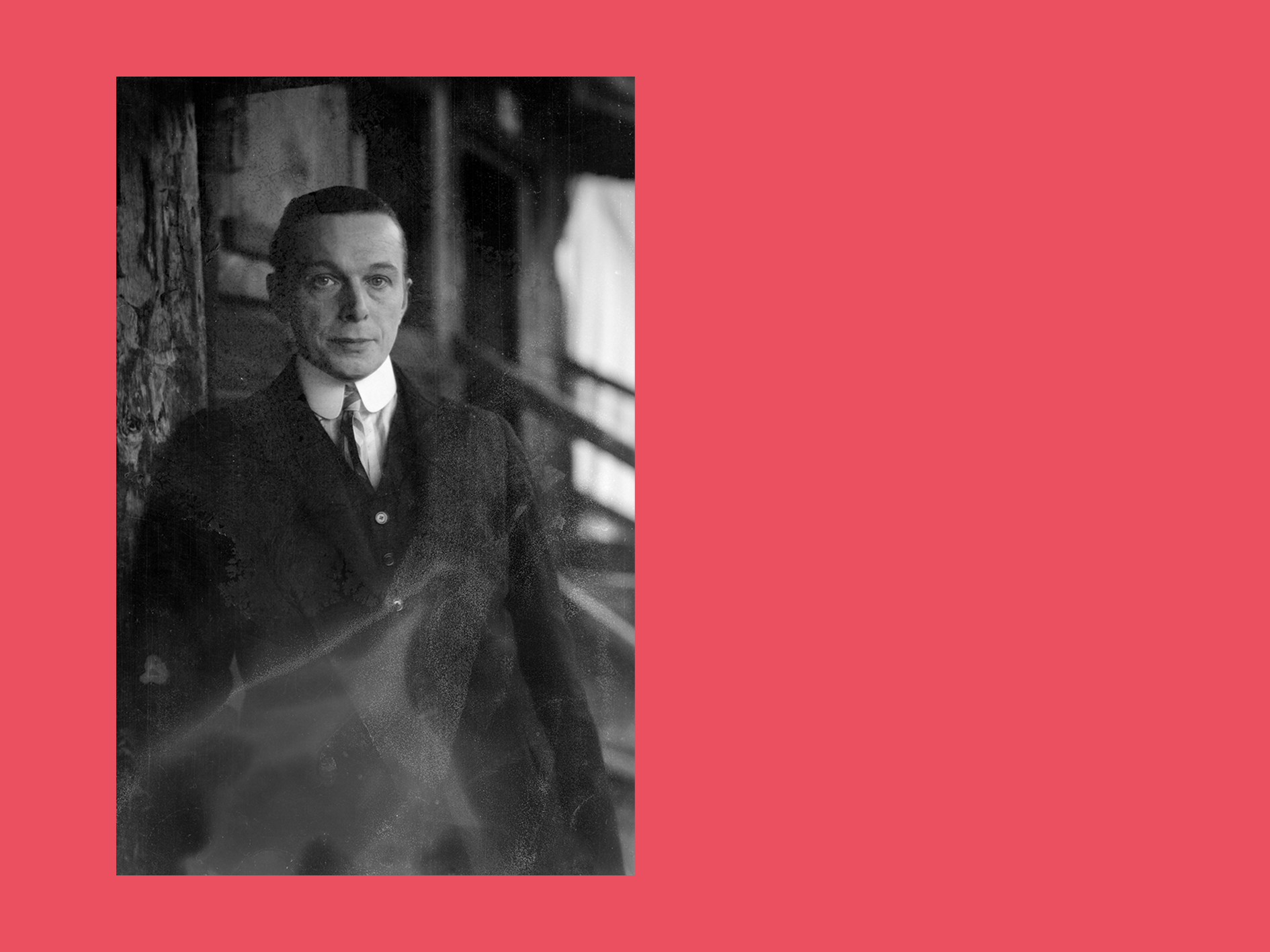

From Self-Taught Artist to Artistic Figurehead

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was born on 6 May 1880 – a year and a half before Picasso – in Aschaffenburg. His path led him to Dresden and Berlin and eventually to the Swiss mountains near the village of Davos, where he lived until his death in 1938. Kirchner was self-taught; he had, in fact, studied architecture in Dresden after completing his secondary education. Together with fellow students Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, he founded the artists’ association “Brücke” in 1905, with the aim of finding a form of artistic expression that was as authentic and immediate as possible. Kirchner is now regarded as one of the most important artists of German Expressionism.

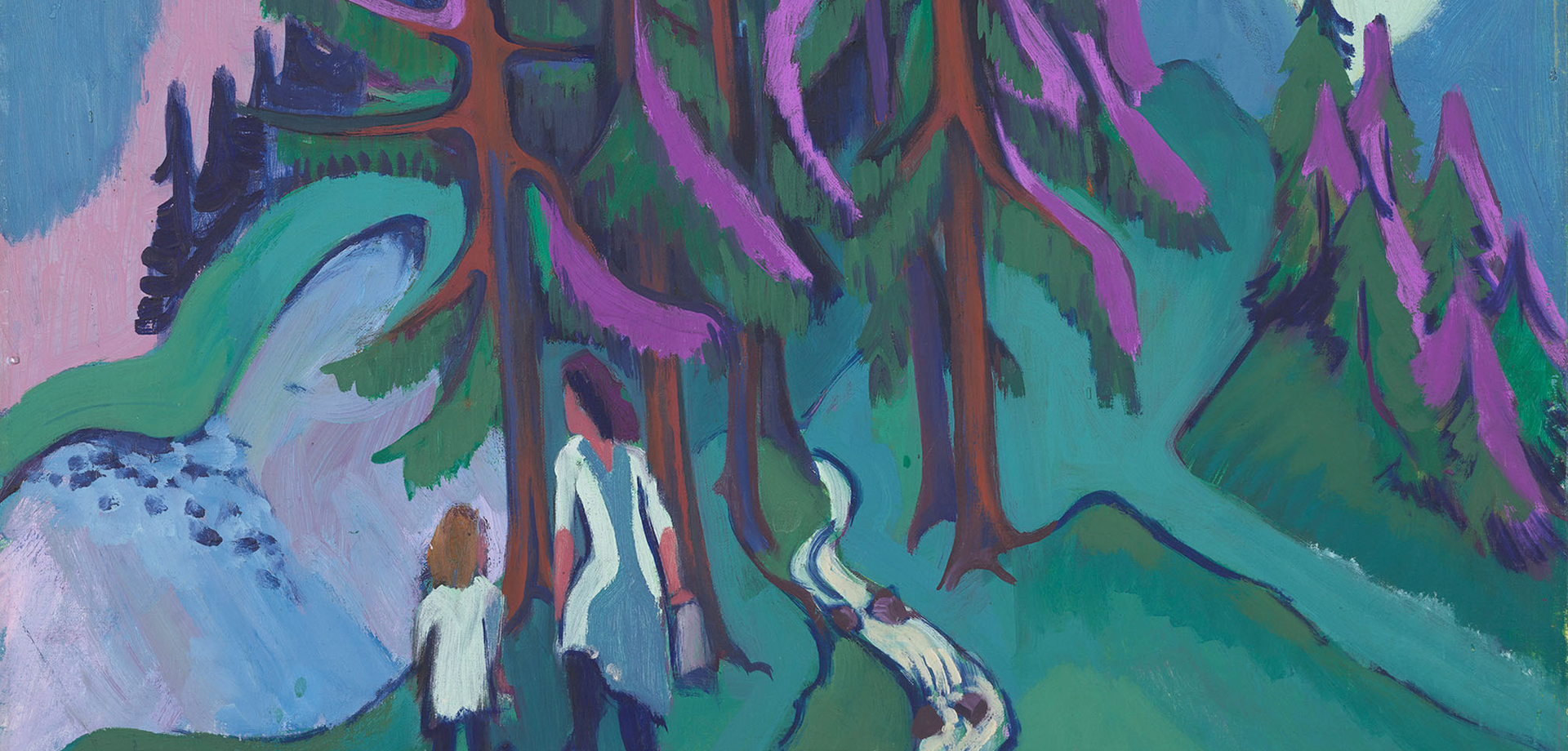

Away from the vibrant life and into the mountains

In 1911, Kirchner moved to Berlin and volunteered for military service after the outbreak of World War I in 1915. However, he never saw action as a soldier: Kirchner suffered a physical and mental breakdown, which ultimately led him to Switzerland in 1917. Surrounded by nature, he hoped to find a quiet, slower pace of life. “Alpine Path After the Storm” (1923/24) is representative of his work in Davos, Switzerland.

Kirchner is fascinated by the changeability of mountain landscapes. Depending on the weather conditions—fog, a moonlit night, or bright sunrises and sunsets—the scenery evokes very different sensory impressions.

What kind of weather did the two hikers enjoy on their way through the Alps that day?

Picasso: More than just a name

Did you know that Pablo Picasso had not just two, but seven first names? His full name was Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz Picasso. He was born on October 25, 1881, in Málaga, Spain, but lived in Madrid, Barcelona, Paris, Brittany, and on the Côte d'Azur in southern France.

The dream of a great artistic career was practically placed in his shoes as a child. His father, himself a painter and art teacher, recognized his son's potential early on and encouraged him from the age of seven. Later, Picasso studied painting at prestigious art academies.

Until his death in 1973, Picasso created tens of thousands of works of art, shaping 20th-century art history like no other.

In 1904, Picasso moved permanently to the art capital of Paris. There, in his studio at the Bateau Lavoir in Montmartre, he produced many works, including the famous paintings that are associated with Cubism.

With the development of this innovative form of expression, the young Picasso achieved one of the greatest upheavals in the art world of the past century.

Digression:

German-French avant-garde exchange

Avant-garde exchange

Even without cell phones or the internet, the art scenes in France and Germany were excellently networked. At the beginning of the 20th century, there was a lively exchange between artists from both countries. Kirchner himself never traveled to Paris, but got to know and love the French avant-garde primarily through his visits to exhibitions in Germany and Switzerland.

A Westphalian in Paris

In 1891, Ida Gerhadi, a native of Westphalia, moved to Paris to study art at the Académie Colarossi. Together with her good friend Käthe Kollwitz, she spent her evenings at the popular dance hall “Bal Bullier.” Like other artists of her time, she immortalized the bustling crowds and cheerful atmosphere on paper.

Chapter 2

Nightlife in the Big City

Dance and Tragedy

The bustling nightlife of Paris and Berlin in the early 20th century captivated both artists. Picasso and Kirchner were interested in everything that was brought into the spotlight by the dazzling glamour of the big city, but also in everything that was cast into the shadows. They turned their attention to the people they encountered in theaters, variety shows, and dance bars—as well as those who roamed the streets of the metropolises at night, far away from the glittering stages. They immersed themselves in this ambivalent world with all their senses and gave expression to the spirit of the times.

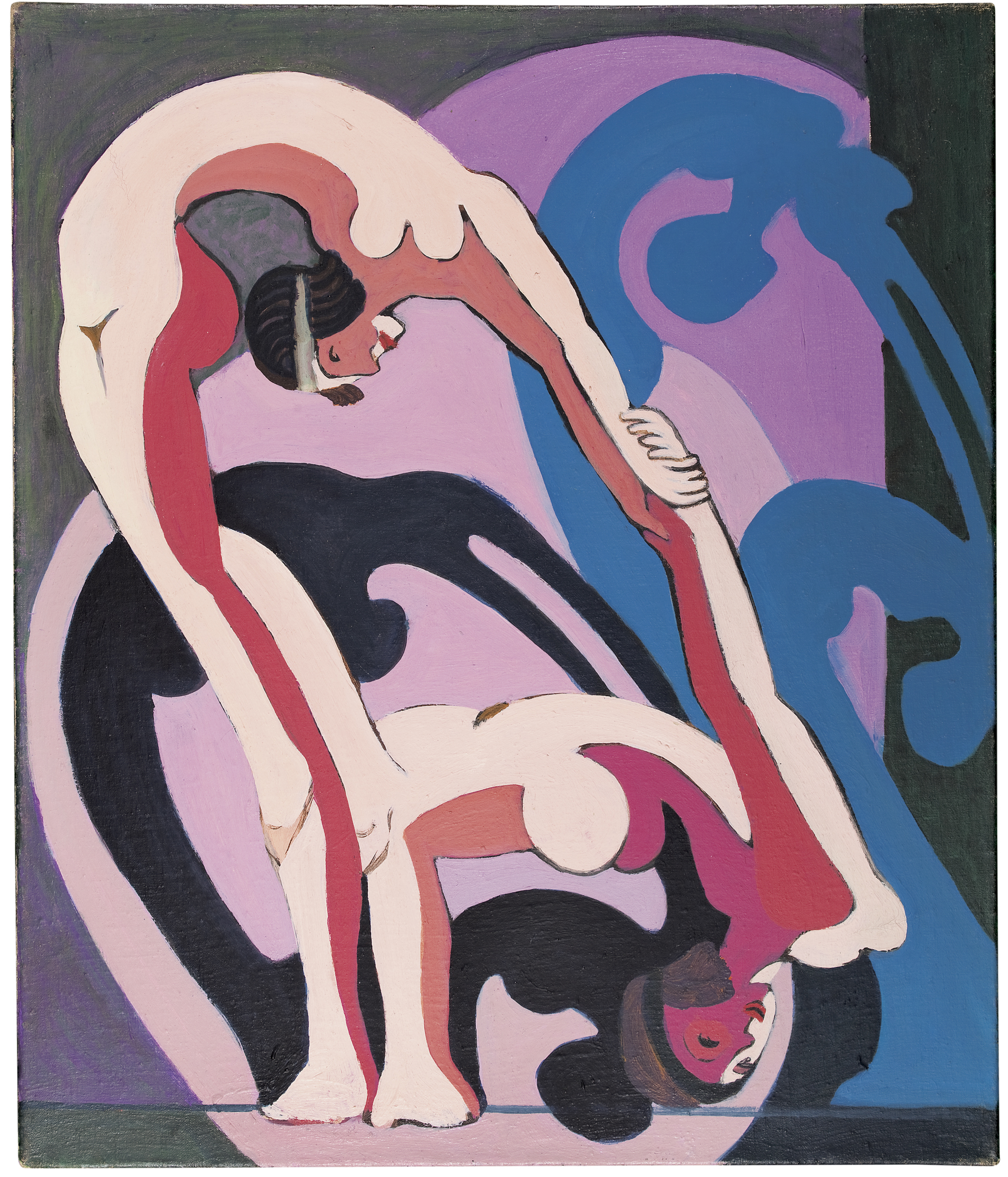

Beauty in motion

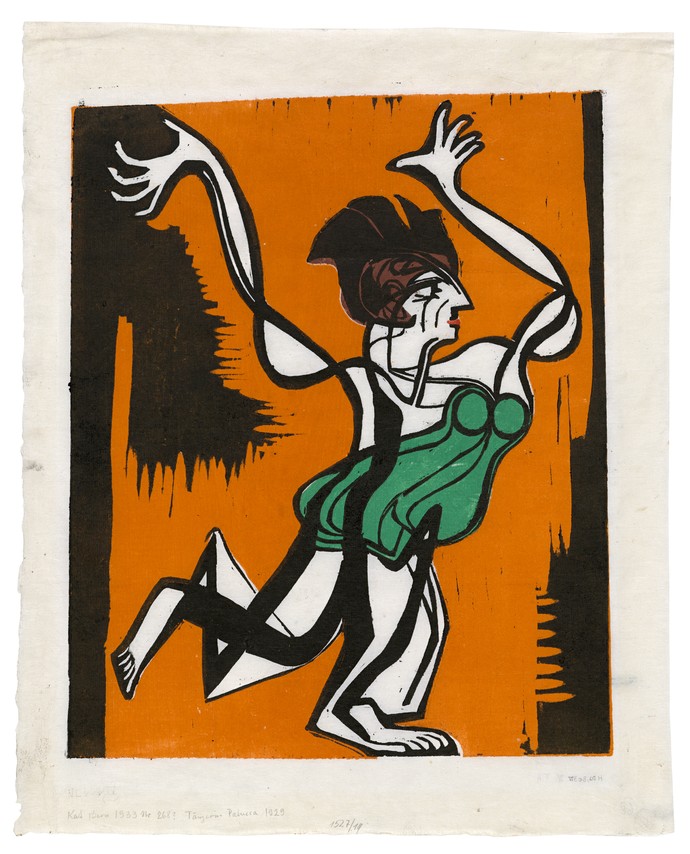

Kirchner and Picasso admire the expressiveness of the moving body, which they repeatedly capture in quick sketches. They strive to free themselves from the strict conventions of society during the day and to reinvent the concept of beauty. In Dresden and Berlin, Kirchner admired the latest dance shows. He was particularly taken with modern expressive dance. As the name suggests, this form of dance is about expressing individual feelings with one's own body.

We see the dancer Gret Palucca immortalized here with dynamic lines. In 1926, Kirchner attended dance rehearsals by the famous dancers Mary Wigman and her student Palucca, although he did not initially like the latter's dances. However, after seeing Palucca on stage in Davos four years later, he changed his mind.

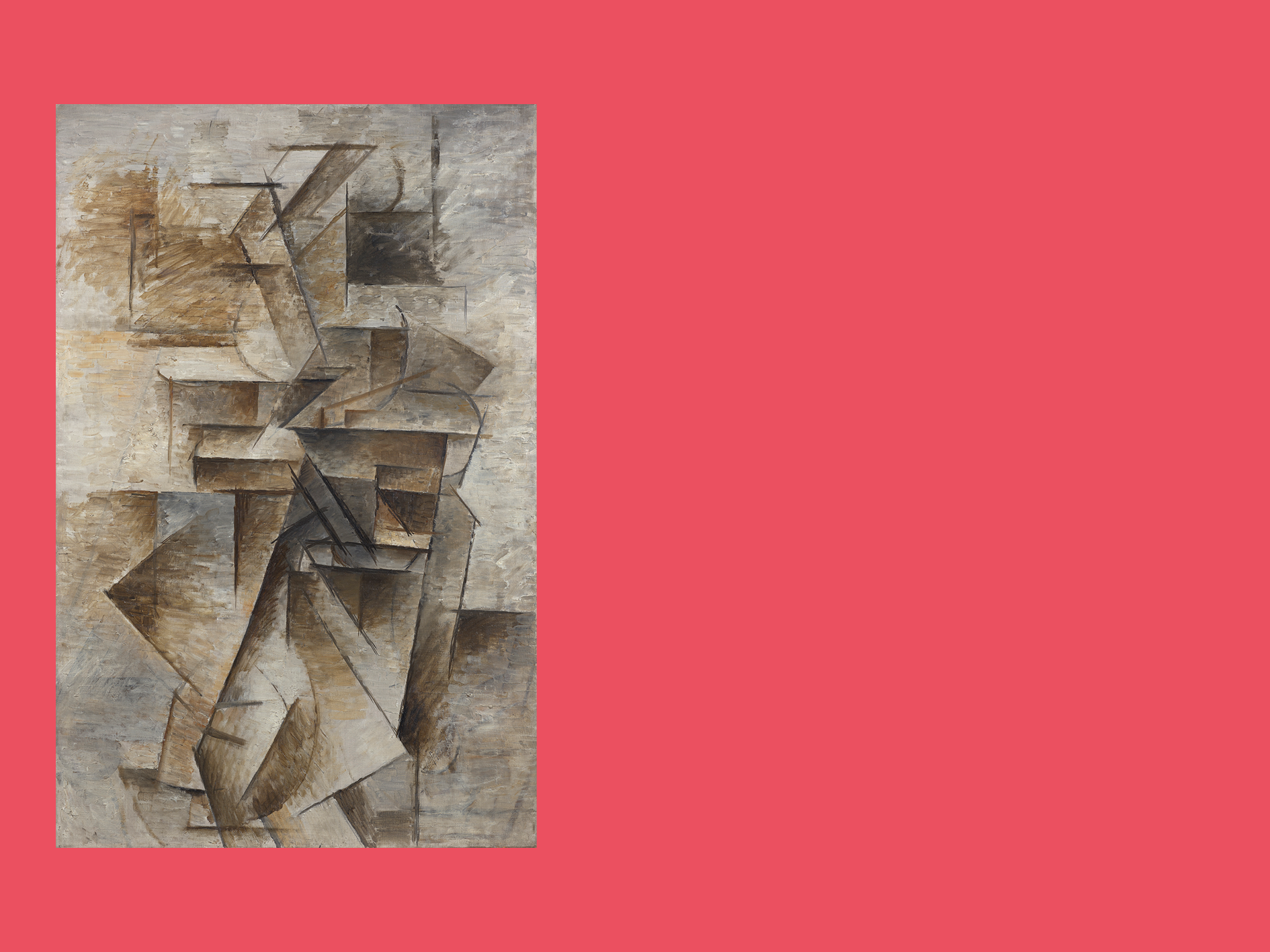

The Sound of Night

The world of music and musicianship also inspired both artists. Picasso repeatedly depicted musicians playing their instruments, constantly developing his style of representation. A good example of this are his mandolin players from 1908 and 1910: the mandolin player from 1910, abstracted almost beyond recognition, approaches the dynamism and simultaneity that Picasso feels in the musicians' artful playing. Kirchner also depicted a mandolin player.

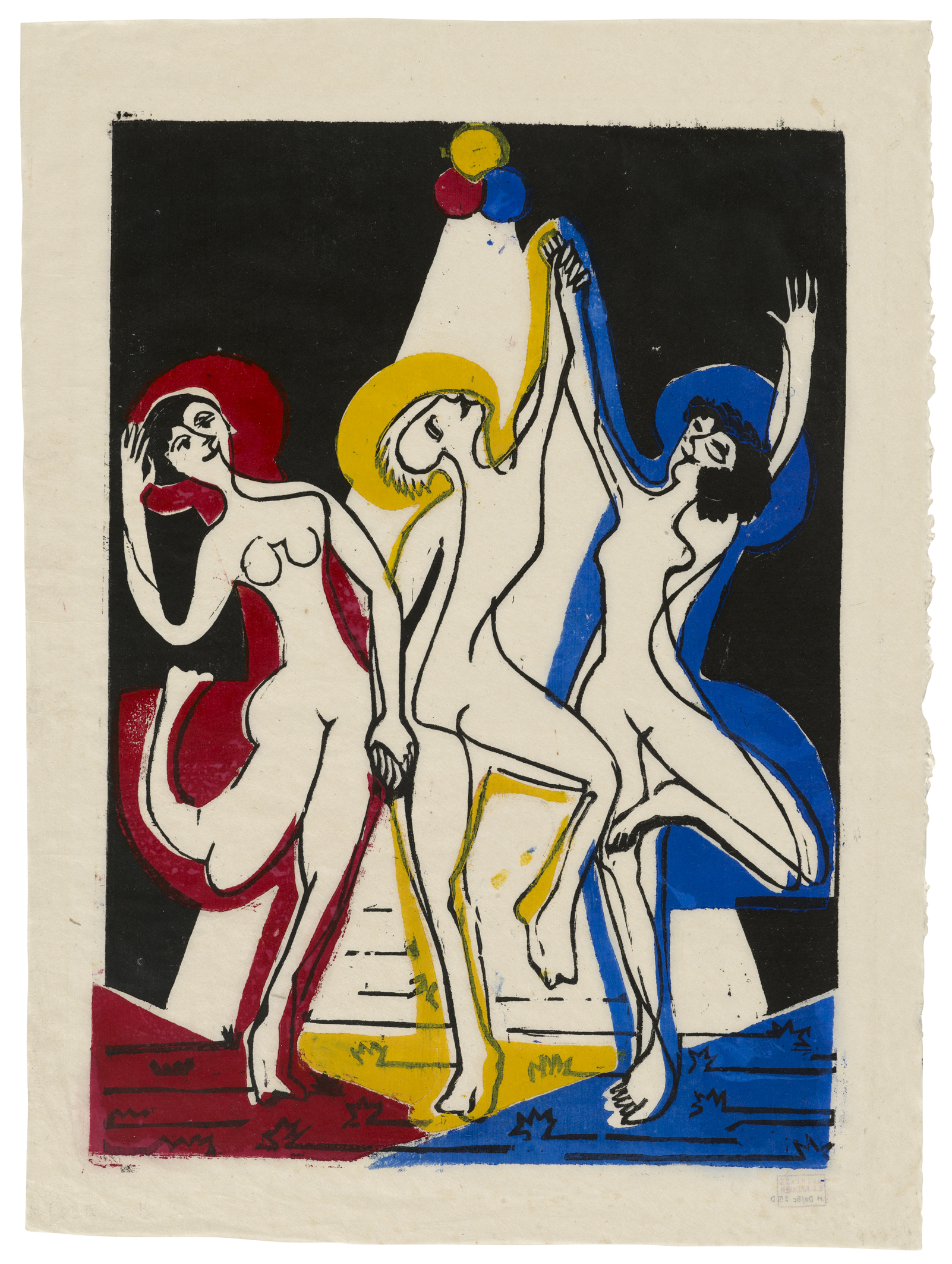

Mirror, mirror

Although Kirchner and Picasso never met, traces of Picasso's visual language can be found repeatedly in Kirchner's works. This is particularly evident in “Farbentanz” (Dance of Colors). The source of inspiration here is probably Picasso's “Three Dancers,” which Kirchner saw in 1932 at a major Picasso exhibition in Zurich.

Other works by Kirchner also show stylistic similarities to Picasso's work. A good example of this is Picasso's cubist gouache painting “Piano” from 1920. Kirchner's painting “Singer at the Piano,” created ten years later, is reminiscent of Picasso's “Piano” in some details.

Can you find them all?

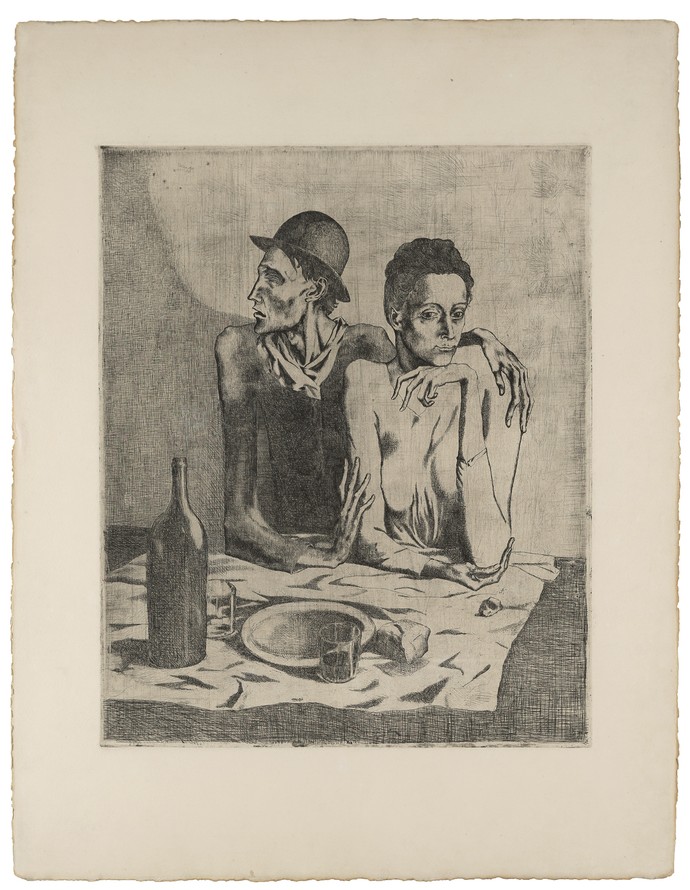

A glimpse into the shadows

Kirchner and Picasso sought to express the entirety of modern life in the metropolises. In addition to the ecstasy and sparkling lights of bars, stages, and circuses, both artists found inspiration in the marginal figures of big-city life who populated the gloomy alleys away from the spotlight. Their paintings therefore also bear witness to the social injustices of the early 20th century and present ways of life that deviate from bourgeois norms. Thus, jugglers, beggars, and sex workers become the protagonists of nightlife here.

Chapter 3

People and Their Images

Curiosity about personality

Human beings, with their uniqueness, have always inspired artists. Curiosity about personality is evident in portraits. This motif also shapes the creative work of Kirchner and Picasso. Their works thus reflect different stylistic and biographical phases in the artists' lives.

Loved and painted

Lover, muse, wife—both Kirchner and Picasso made their partners immortal motifs on canvas, even if “immortal” did not necessarily apply to their relationships. On the one hand, their closeness to their models reveals intimacy and closeness; on the other hand, the portraits are fields of experimentation for stylistic change and radicalism.

Kirchner and Picasso departed from the academic ideal and moved beyond naturalistic representation. Kirchner reacted strongly to his respective living conditions and surroundings, while Picasso drew inspiration from his passionate and sometimes conflict-ridden relationships.

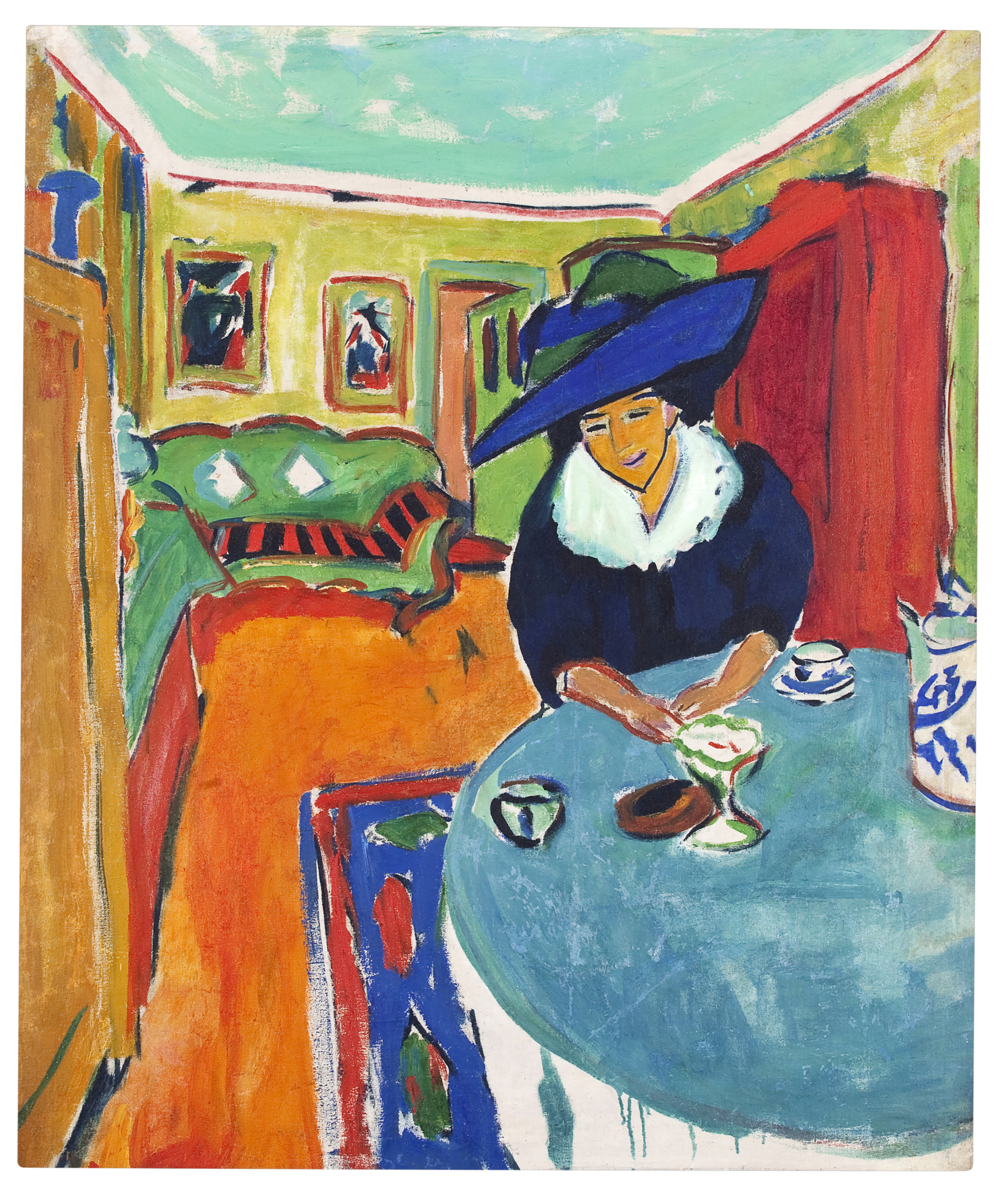

Dodo – the embodiment of freedom

This gently smiling lady is no stranger to Kirchner: she is Doris Große – affectionately known as “Dodo.” In Dresden, she became his muse and partner from 1909 onwards. She posed for him naked, direct, and unadorned, or, as here, with her trademark large hats.

Große embodies both freedom and closeness. With her, Kirchner dared to take a step into a new visual language – expressive, radical, uncompromisingly modern. He began to break with academic ideals of beauty and painted with great energy. When Kirchner moved to Berlin in 1911, she remained in Dresden.

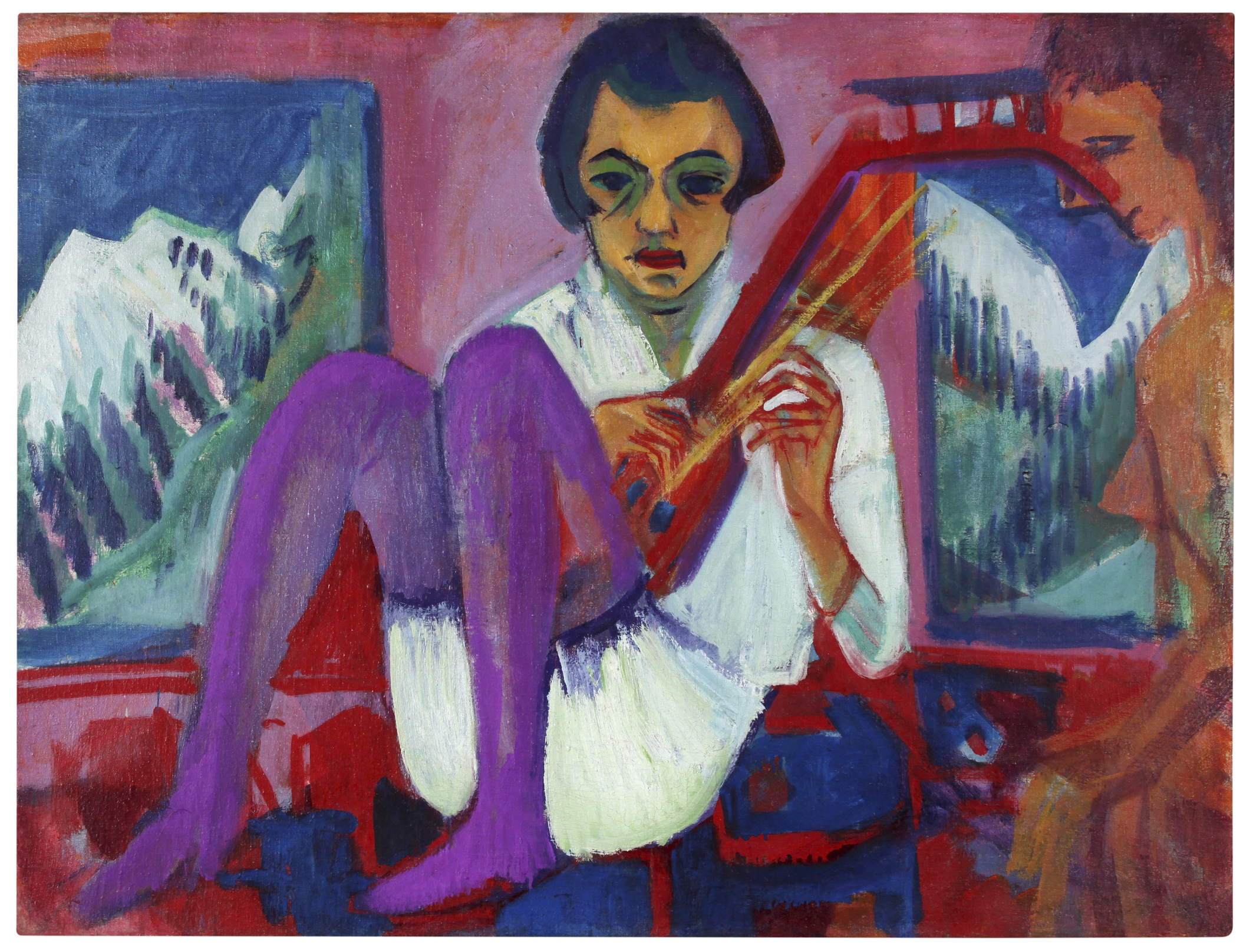

Erna – More than a Muse

After moving to Berlin in 1912, Kirchner met Erna Schilling. She was a dancer in variety shows, often performing with her sister Gerda. Both sisters regularly posed for the artist, and Schilling became his long-term partner. She was confident, modern, and embodied the new urban type. Schilling influenced the way he lived his life and introduced him to Berlin’s bohemian circles.

She remained by Kirchner’s side during his most difficult times: his nervous breakdown during the First World War, his stays in sanatoriums, and his move to Davos. She cared for him, organised his surroundings, and assisted in communicating with collectors and friends. She died in Davos in 1945, seven years after Kirchner’s suicide. Erna Schilling was far more than Kirchner’s model – she was his partner, support, and a mirror to his art.

Kirchner's typical Berlin style

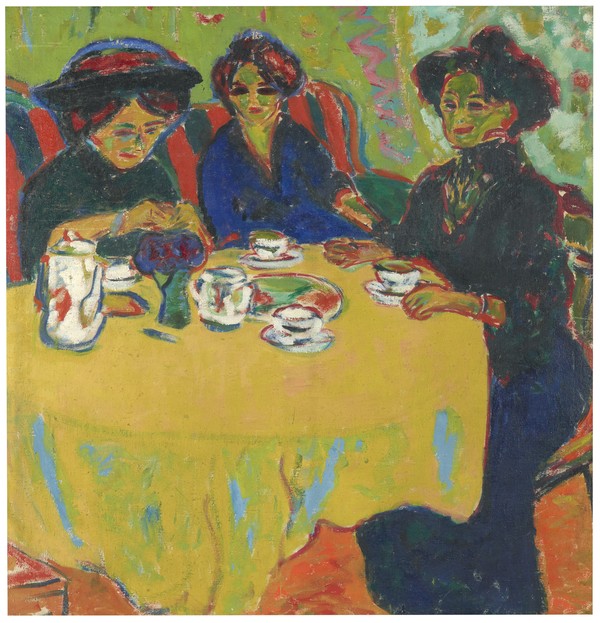

Color frenzy

With “Kaffeetafel” (Coffee Table), Kirchner transforms this bourgeois ritual into a vibrant experiment in modernism. The three ladies drinking coffee are painted with quick brushstrokes, bright colors, and angular contours.

The painting is more than just an everyday moment: it shows how Kirchner and the “Brücke” group of artists were searching for new forms of expression. Away from staid academicism, toward direct, subjective painting full of expressive and bright colors—a feeling of energy and new beginnings dominates.

☺ Fun Fact

Five years later, Kirchner painted the back of the canvas as well, out of financial necessity. Nevertheless, the older, discarded coffee table is now considered his major work, not the later Fehmarn painting. He visited the island of Fehmarn several times until the outbreak of war in 1914. The painting shows his partner Erna Schilling, friends, and probably also the artist Otto Mueller, whom we can see in the picture wearing a hat and smoking a pipe.

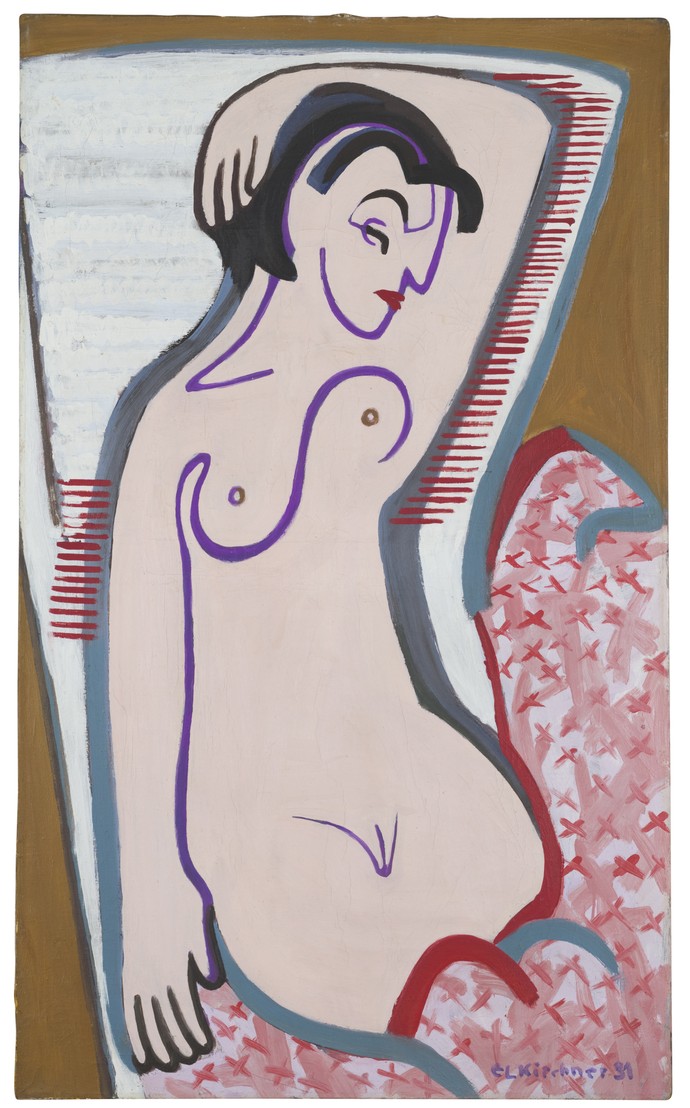

1930s style

In the 1930s, Kirchner refined his style. His paintings appear clear: circles, lines, and geometric shapes dominate the imagery. He creates accents with a deliberate color strategy and sharp contrasts.

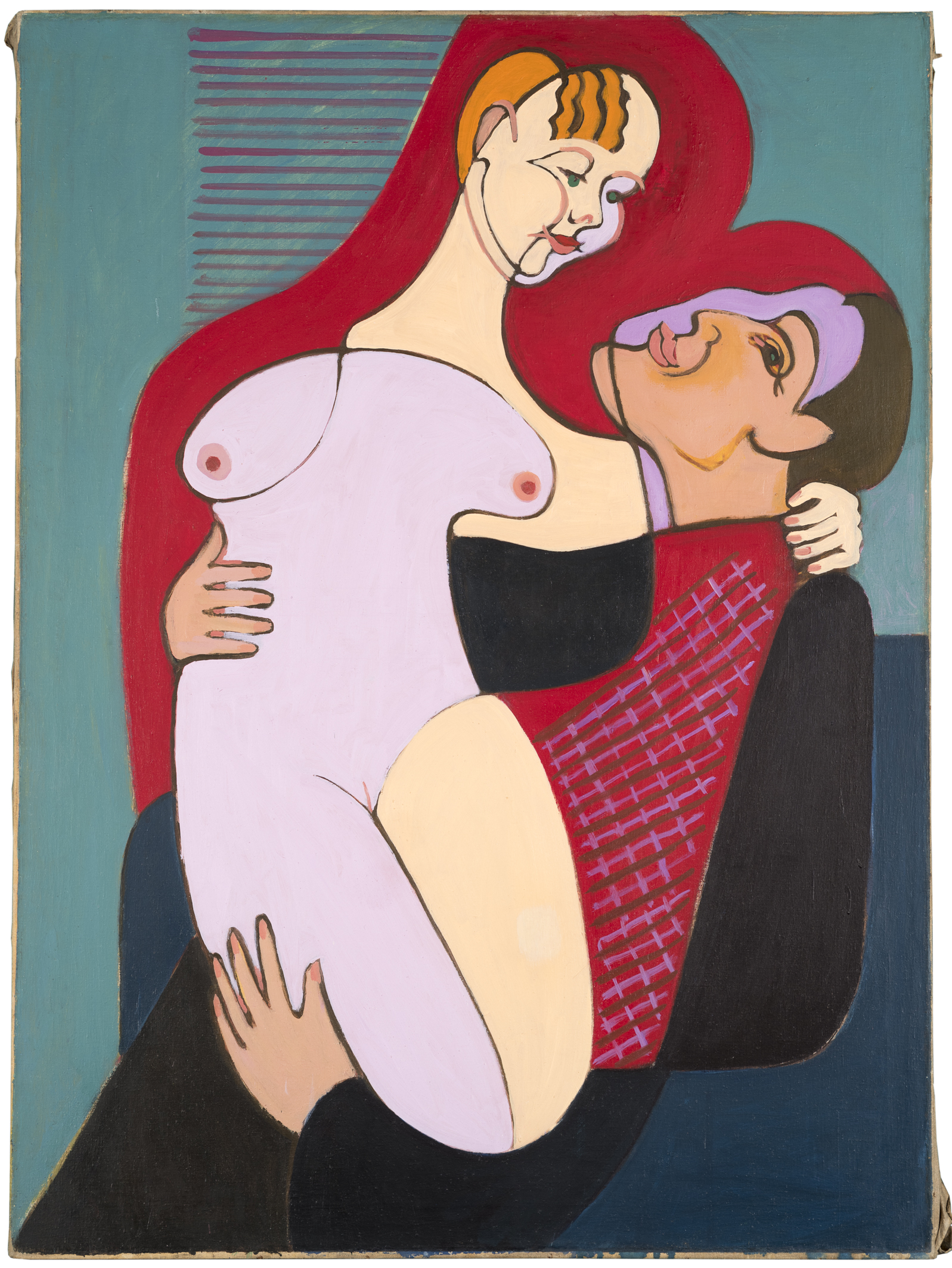

Image of Woman

A dress – and yet almost naked. Kirchner depicts Elisabeth Hembus as a sensual, self-assured woman with a cigarette, while simultaneously reducing her to her body. The red dress becomes a second skin.

Disruptions

Julius and Elisabeth Hembus lived near Davos, like Kirchner. At first, they were close friends, and Elisabeth even became one of his favourite models. But later the relationship broke down.

The double portrait also marks a turning point in Kirchner’s painting. From 1927 onwards, he abandoned the hectic, expressionist linework in favour of calmer compositions made up of soft colour fields. His tones became brighter and more radiant, often far removed from reality. He also drew inspiration from Picasso’s surrealist works, which he saw in Zurich in 1925.

Elisabeth Hembus lies in her husband’s arms. He wears a suit, while she appears as a naked, curving, pale form, without arms or calves. This not only renders her entirely motionless but also reduces her body to her sexuality. Kirchner thus presents her as a purely decorative and passive form, while the male figure remains clothed and active.

Picasso and Women

Like Kirchner and many other male artists of the time, Picasso also painted portraits of his female companions. Some were his wives, others secret lovers, and still others temporary partners. They influenced his style and his artistic phases.

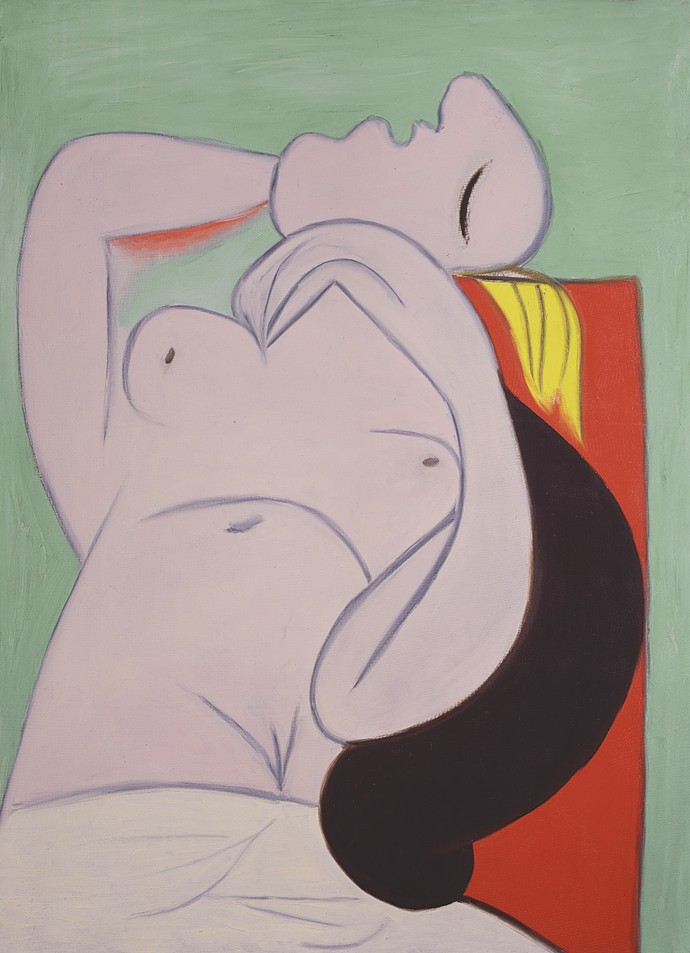

Marie-Thérèse Walter – The Tragic Beauty

What begins as a fruitful and stimulating relationship can end tragically, as Picasso's relationship with Marie-Thérèse Walter shows:

In 1927, Picasso meets 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter. He is already 45 and married to ballet dancer Olga Khokhlova. Nevertheless, she became his secret lover, his model, and in 1935, the mother of his daughter Maya. With her, a new artistic phase began for Picasso: he painted soft lines, round shapes, and bright colors. Walter appeared in sensual poses, often sleeping or reading.

What appears tender is at the same time radically broken up by Picasso: he experiments with abstraction. Closeness and distance, intimacy and fragmentation lie close together. After a few years, Picasso distanced himself emotionally from her, even though he continued to create pictures of her. When Picasso died in 1973, Walter fell into a deep depression. In 1977, she took her own life.

Dora Maar – Passion that causes suffering

Picasso broke with naturalism as early as 1906. Inspired by non-European sculptures, such as African and pre-Columbian works, the artist invented Cubism together with George Braque. He developed a completely new formal vocabulary—Picasso reduced forms to their essentials and radically sought a new understanding of the human figure.

This painting dates from his passionate and conflict-ridden relationship with the artist and photographer Dora Maar, whom he met in 1936 while he was still involved with Marie-Thérèse Walter. Here, too, we see Picasso's view of gender relations: he portrayed women in a way that oscillated between admiration and appropriation.

The individual no longer appears as a harmonious entity, but as fragmented, contradictory, vulnerable. Thus, his relationship with Dora Maar also ends in shambles. After the breakup, Maar almost breaks down. But she finds her way back to art and leaves behind a body of work that is finally being seen in a new light today.

Françoise Gilot – The woman who left Picasso

In 1943, Picasso met 21-year-old painter Françoise Gilot. She became the mother of his children Claude and Paloma. With her, he painted in a brighter, more playful style, full of lightness.

But Gilot did not remain in the shadows. She fought for her freedom, continued to paint confidently, and resisted his control. In 1953, she left Picasso—the only woman to do so.

Later, she wrote the book Life with Picasso, built her own career, and remained an independent artist into old age.

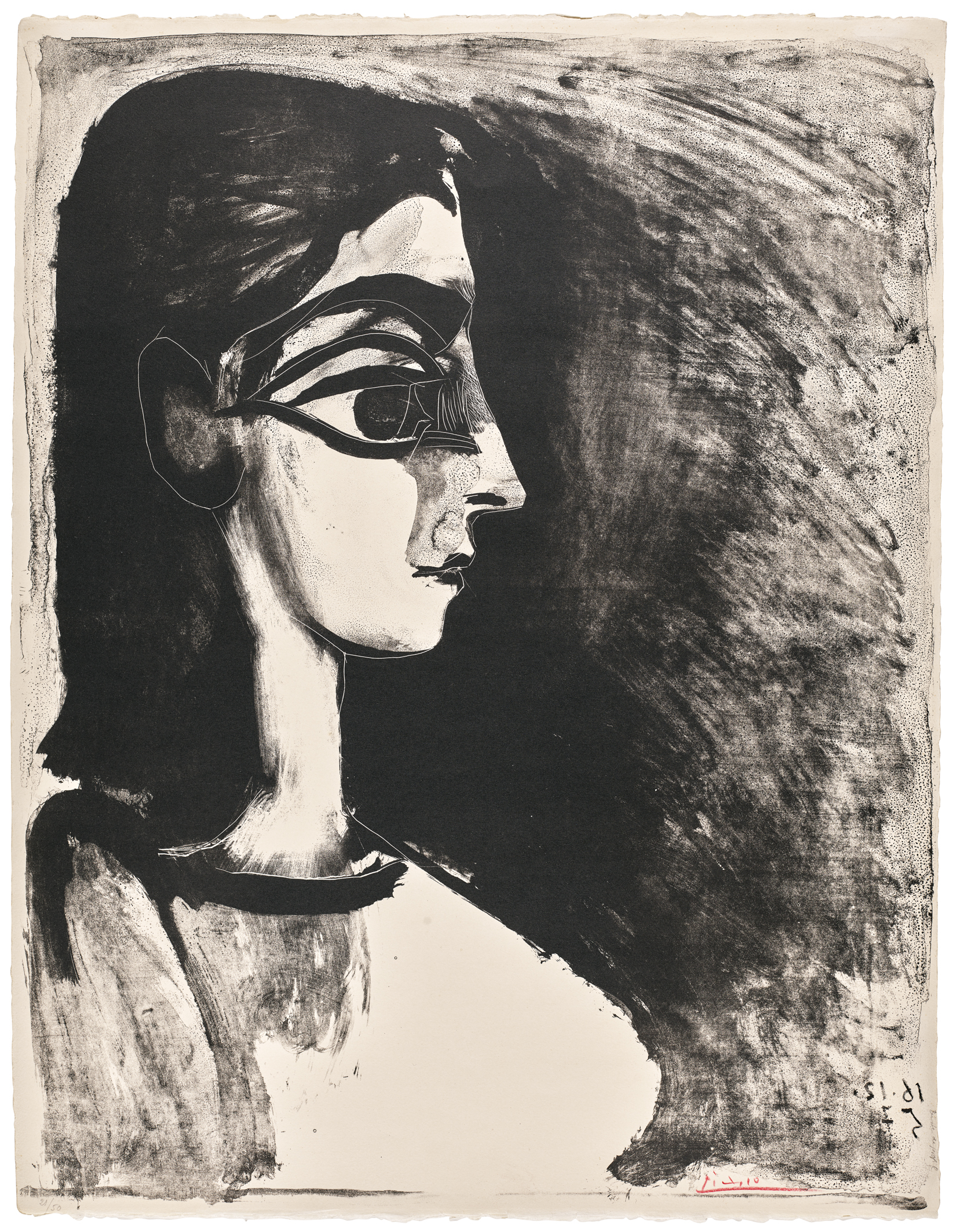

400 times Jaqueline

Picasso painted his second and last wife, Jacqueline Roque, over 400 times. No other woman appears in his work so frequently. She was 27 and he was almost 70 when they met. With this painting, Picasso began a series of portraits on zinc plates—and Roque was naturally the focus. Picasso constantly tinkered with his motifs, reworking them again and again. But instead of hiding the earlier versions, he had them published in editions of 50.

Although Roque was 45 years younger, she was his longest-standing companion, giving him stability and support and accompanying him until his death in 1973. Roque took her own life in 1986.

Chapter 4

The Studio and the Nude

Fascination with the Nude

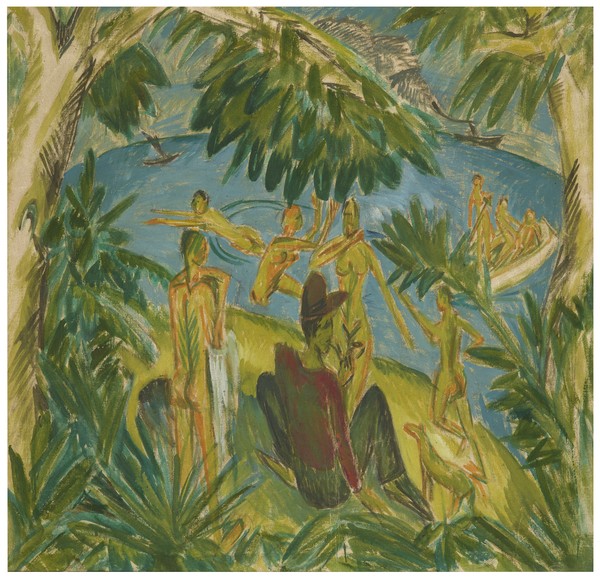

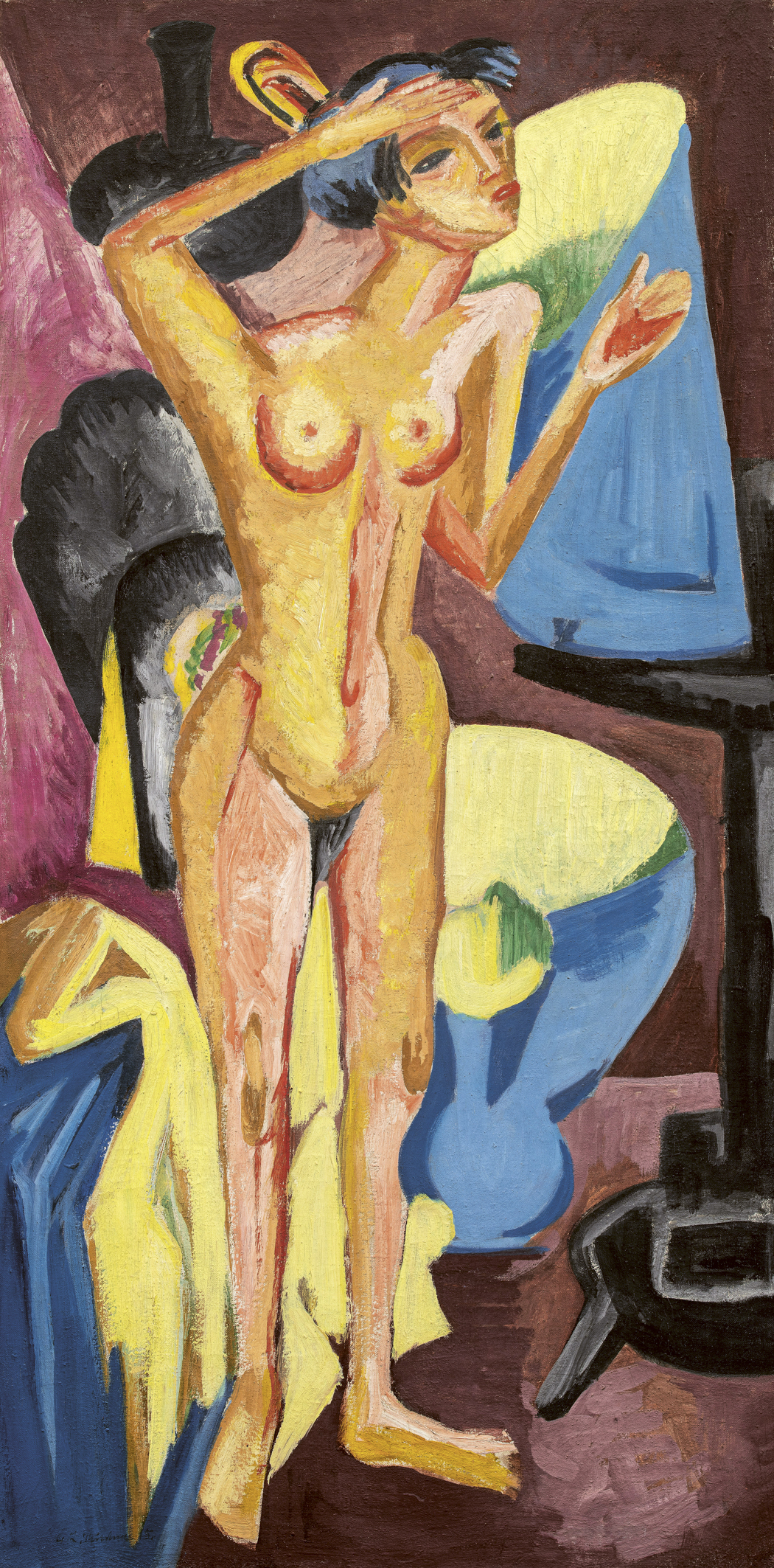

Fascination with the nude – two perspectives, one subject: the naked body between nature, intimacy and artistic freedom. Kirchner and Picasso repeatedly depicted the nude, sometimes outdoors, sometimes in the studio and each in their own distinctive way.

Kirchner was drawn to nature: as early as the 1910s, he sketched bathers on the beach of Fehmarn or at the Moritzburg Lakes. For him, nude bathing symbolised freedom, joy of life, and a break with the stiffness of studio-produced art. He sought genuine, vivid scenes drawn directly from life.

Picasso, on the other hand, preferred to stay indoors. His nudes appear in indeterminate spaces, often studios. His focus lay clearly on the model and the relationship between artist and sitter. Unlike Kirchner, he was less interested in the surroundings than in intimacy, tension, and sometimes power.

“It is therefore not right to judge my works by the standard of naturalistic accuracy, for they are not representations of specific objects or beings, but independent organisms of lines, planes and colours, containing natural forms only insofar as these are necessary as keys to understanding.”

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

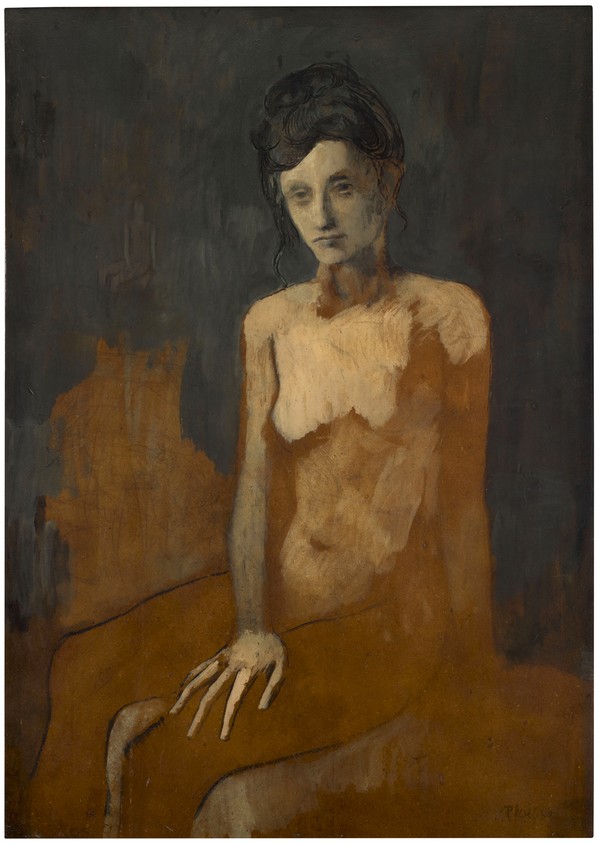

Lonely Rather Than Erotic

Before a dark background sits a young naked woman. Her face and hair are clearly defined, but her body remains vague – as though dissolving. She appears slender, pale, tired. Her gaze drifts past us. Instead of eroticism, she exudes restraint and vulnerability. It is an early work by Picasso from 1905.

In 1921, Picasso surprisingly changed course: instead of continuing further into abstraction and abandoning figuration entirely, he returned to conventional forms. Yet these figures appear not natural but monumental – like sculptures from antiquity. In Seated Woman (Woman in a Chemise), the massive figure fills almost the entire canvas. Exaggerated facial features and bulbous fingers reinforce the sense of weight. Her posture and the folds of her white garment lend the scene a stern, motionless quality.

Kirchner’s passion lay in drawing nudes and exploring the moving body. By 1905 at the latest, he had broken away from academic ideals, and the line took centre stage – at first soft and flowing, later, in Berlin, harsher and more radical.

Artist and Model Relationship

Freedom in the studio sounds liberating – but in the past, it was often one-sided. Men painted, women were looked at. Only men were admitted to the academies; women found themselves in front of the easel, not behind it.

Those who agreed to pose often entered a relationship of dependency, with all the risks of boundary violations. Particularly problematic were underage models, since the power imbalance was even greater.

Today, we look at this more critically. A glance back reveals a system designed above all to advance male careers.

There is something secret behind people and things and behind colours and frames, something that reconnects everything to life and to visible appearance – that is the beauty I seek.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Kirchner discovered Picasso’s "Le sommeil" in Zurich in 1932 and was inspired by it. Shortly afterwards, he painted a remarkably similar scene. Yet he simply dated his painting "Nude Reclining Woman" back to 1931. Coincidence? More likely a clever move.

Kirchner adopted Picasso’s unusual pose but interpreted the image using his own stylistic means.

Chapter 5

Artist Personalities

Kirchner and Picasso – masters of self-promotion

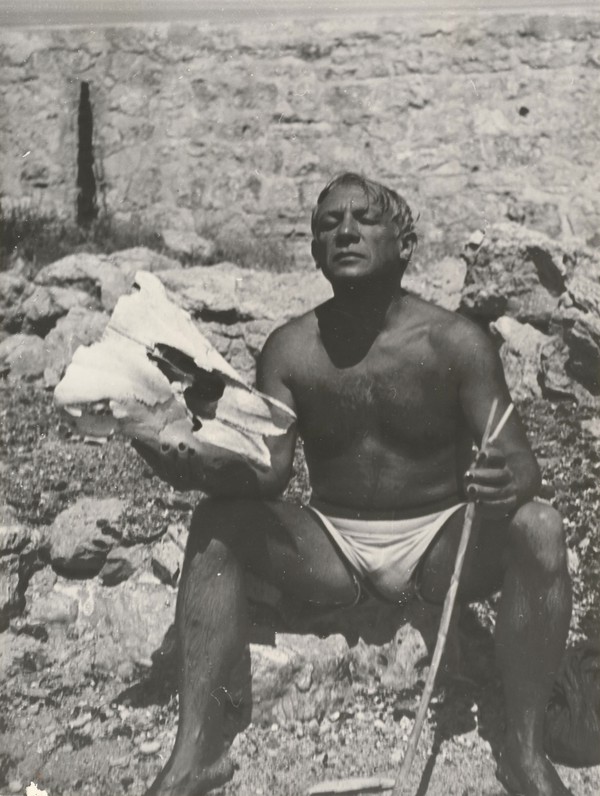

Kirchner and Picasso radically stage their roles as artists, thereby shaping their own public image. Kirchner presents himself as a bohemian, an outsider, and a vulnerable artist. His photos and self-portraits appear raw, direct, and at times full of nervous energy.

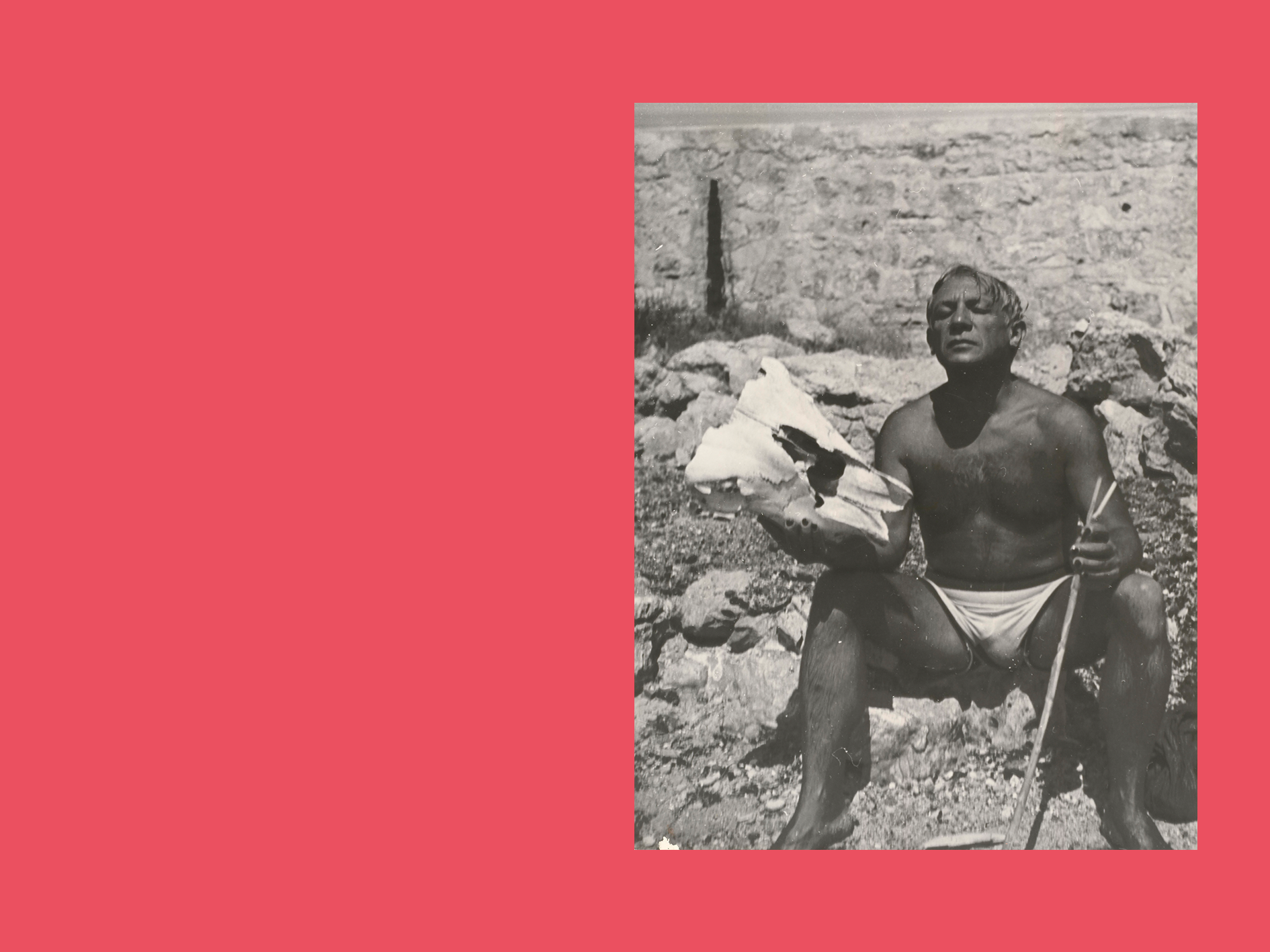

Picasso presented himself as a larger-than-life genius. He changed roles like masks: Minotaur, prince of painters, tireless creator. Always in control, always at the center.

Hardly any other artist has been photographed as often as Picasso. Whether in his studio, with his family, or at public appearances, he consciously staged his image through the camera. Thousands of photographs have been preserved. They made him an icon of photographic artist portraits and allow the world to share in the “myth of Picasso” to this day.

Kirchner lives his life without regard for convention. He often depicts himself—sometimes as a celebrated artist, sometimes as a sick, scarred man. His self-portraits tell the story of how he feels and how he wants to be seen.

But he goes even further: from 1920 onwards, he writes texts about his own art under the false name Louis de Marsalle. In this way, he presents himself as an independent artist—detached from Die Brücke, ready for his international breakthrough. As more and more people become suspicious, he pulls the emergency brake: in 1933, the fictional critic “dies.” A final grand appearance in the game of illusion and self-image.

New forms, new paths

Kirchner and Picasso: two exceptional artists whose works not only testify to their tremendous innovative spirit, but also reveal two perspectives on the social conditions of their creative period. Shared sources of inspiration, themes, and visual languages tell of the attitude toward life in the 20th century and give it two striking forms of artistic expression.

Would you like to learn more?

Information about tours, workshops, and the cultural program accompanying the exhibition can be found here.

Discover more exhibits in the digital collection online.

An exhibition by the LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur, Münster, and the Kirchner Museum Davos.

Kirchner Museum Davos

15.2.–3.5.2026

Sponsored by the LWL-Kulturstiftung, the Stiftung Kunst³, the Stiftung der Sparkasse Münsterland Ost and the Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung.